The Stew BLOG

The Importance of Residents’ Sense of Belonging, Trust, and Power

Pt 3 of 4-part Resident Engagement Blog Series

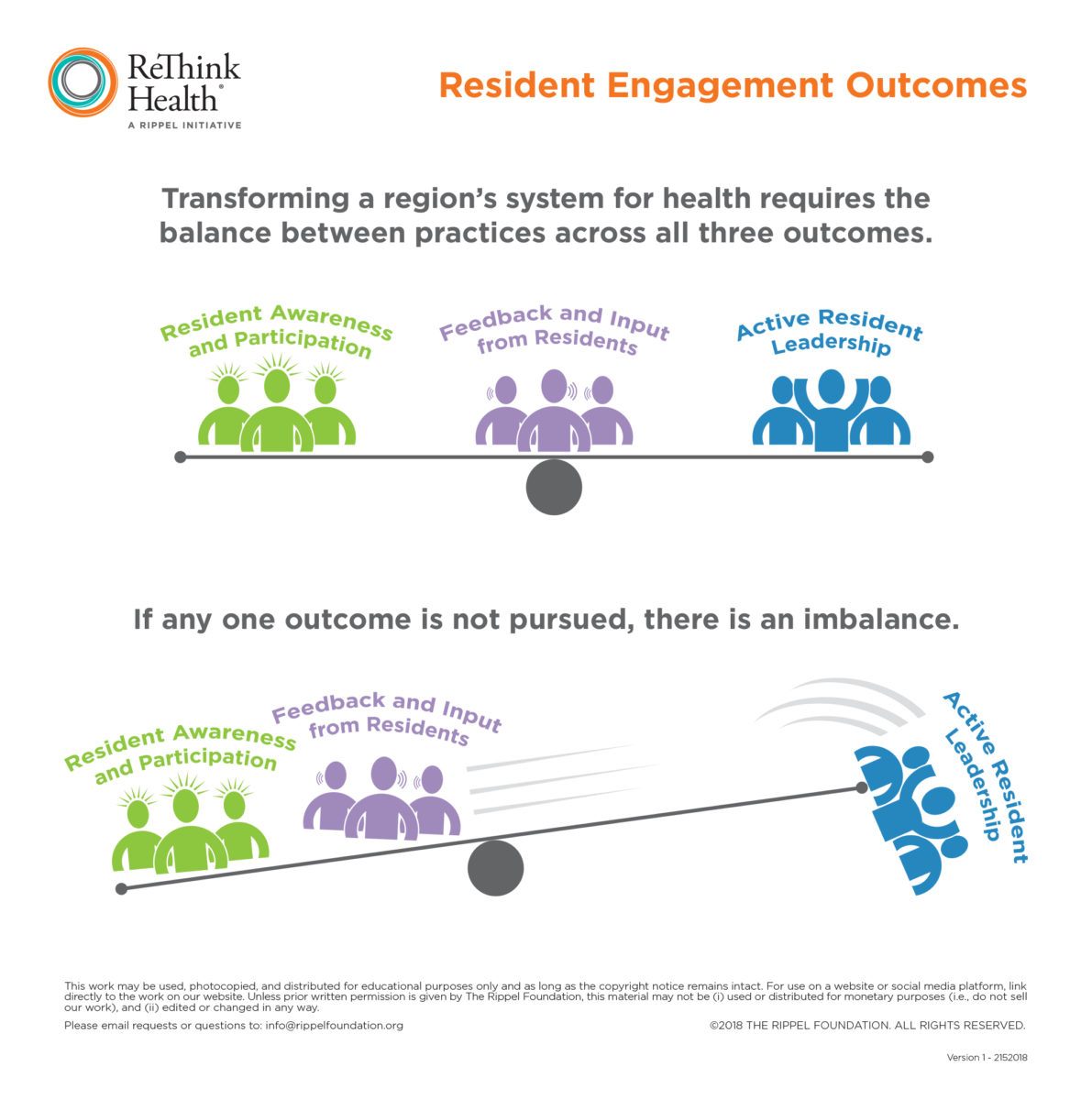

In our previous post, we shared that the vast majority of multisector partnerships and organizations involved in resident engagement are focused on two approaches: increasing resident awareness and participation and/or getting feedback and input from residents rarely are they focused on a third: pursuing active resident leadership. We also described how creating a balance between these three different approaches best supports health system transformation efforts.

This post describes why maintaining a balance is so important. To sum it up: focusing across the three approaches creates the best possible conditions for residents to help lead the transformation in meaningful and effective ways. These conditions are also created by the way partnerships carry out the practices associated with each approach (if you’re not sure what the practices are, check out our Resident Engagement Practices Typology).

This post describes why maintaining a balance is so important. To sum it up: focusing across the three approaches creates the best possible conditions for residents to help lead the transformation in meaningful and effective ways. These conditions are also created by the way partnerships carry out the practices associated with each approach (if you’re not sure what the practices are, check out our Resident Engagement Practices Typology).

In our research, we observed that the partnerships and other organizations that are most effective at creating the conditions for residents to lead transformation ensure their practices are helping residents experience all of the following: (1) a sense of belonging; (2) a sense of trust; and (3) a sense of power.

Here’s an overview of why each of these matters:

Here’s an overview of why each of these matters:

Sense of belonging: For almost anyone, a sense of collective and cultural identity is a powerful source of motivation for active involvement and leadership. If residents feel like they don’t belong to a place or a region, it is difficult for them to invest time and energy to work on improving things around them. (And it doesn’t hurt that sense of belonging contributes directly to health outcomes–since that’s the ultimate goal. Research has shown that people who feel attached to, and interact more with, others enjoy better health than those who are more isolated.)

Sense of trust: As has been widely documented by Robert Sampson, professor of social sciences at Harvard University, low levels of relational trust among residents, and between residents and local institutions, is an enormous barrier to engagement and transformation. Change happens at the speed of trust, so all resident engagement practices should create opportunities for cultivating trust and accountability. For example, partnerships and residents can develop a mutual relationship in which both parties take risks–the organizations trust the decisions and behaviors of residents rather than dictating to them and residents trust the intentions and support offered by the organizations and professionals.

Sense of power: The power, or sense of agency,, to influence your community is essential for exercising leadership. Without a sense that their efforts and opinions really matter–which partially depends on feelings of belonging and trust–people rarely find the motivation to be actively involved in the initiatives or sustain the long-term efforts needed for community transformation.

Importantly, there is no particular order in which residents experience a sense of belonging, trust, and power, and the three are incredibly interconnected. For example, to develop power, you need to have trust. Further, you can often gain a sense of power when you have a sense of belonging, and you can feel a sense of belonging even if you don’t feel a sense of trust.

Putting Belonging, Trust, and Power into Practice

Partnerships and other organizations interested in engaging residents can design, improve, and evaluate their practices through the lenses of belonging, trust, and power. Let’s consider one of the most common resident engagement practices–a survey conducted across the community–to explore how partnerships working on health system transformation can approach resident engagement.

To conduct a survey, partnerships tend to set up an internal team, develop a set of survey questions to explore the health-related priorities of residents, transfer the questions to an online platform (e.g., SurveyMonkey), and distribute the survey through various communication channels. After the information is collected, someone in the partnership analyzes the results and develops the presentation of residents’ priorities that will be used to, among other things, inform decisions about community investments or improving specific services.

If a partnership implements a survey with residents’ sense of belonging, trust, and power in mind, the process looks quite different. Instead of designing the survey on its own, the partnership would ask itself three questions:

- How is this practice creating a sense of belonging for residents in our region?

- How is this practice fostering a sense of trust among residents in our region and trust in our organization or partnership?

- How is this practice increasing residents’ sense of power to change and influence the region where they live?

Answering these questions could lead the partnership to involve residents and community organizations (which often represent residents) to co-design the survey. Then, the partnership might distribute the survey in partnership with local residents, by intentionally working with people from the community to ensure that information is collected from everyone and not just from people who usually participate or have online access. The partnership might also provide resources to residents who are open to organizing outreach events that will nurture and celebrate local values and history.

When the survey is complete, the partnership might create a transparent process of sharing the results with the community. For example, it could coordinate a series of town hall meetings in partnership with local churches, civic centers, or active community organizations. Instead of just presenting the information, the partnership might invite people to join in a dialogue about how to implement some of the findings, and invite residents to take action. The partnership could also ask residents to help create a process for holding the partnership accountable for implementing the decisions that impact the community and develop a long-term plan for regular “check-ins” with residents.

If performed well, this process will increase residents’ sense of belonging, trust, and power as well as increase the likelihood of success for the partnership’s health transformation efforts in the communities it serves.

Successful examples

The hypothetical example above helps us illustrate what it would look like to help residents experience a sense of belonging, trust, and empowerment, from start to finish. We hope that by incorporating a few successful real world examples as well, you will get a better idea of how you might begin to set the conditions for residents to help lead transformation through your own efforts.

Example 1: Stamford, CT

In Stamford Connecticut, Vita Coalition (a.k.a., The Stamford Community Collaboration) developed a very courageous accountability process with residents. As Vincent Tufo, one of the coalition leaders, explained: “In the early 2000’s, when we began a period of extensive public housing revitalization that would result in temporary [public housing] resident relocation, the level of trust between the housing authority and residents was not particularly positive. To demonstrate the strength of our commitment to full resident re-occupancy, we created a cash escrow for use by residents in enforcing that commitment. The escrow, held by an independent law firm, would provide residents with the financial wherewithal to pursue legal remedies, if needed. I consider that the best initial example of how we moved beyond simple expressions of intent, such as participating in a resident meeting with an architect and describing what the new buildings would look like, to putting our financial resources at risk. Recognizing that, in a failure of our commitment, residents would suffer significant losses–loss of stability, loss of security–required an extraordinary demonstration that the escrow provided .”

Example 2: Minneapolis, MN

Gretchen Musicant, Commissioner of the Minneapolis Health Department, shared how her team designed a resident engagement effort to develop an urban health development strategy. She said, “We asked each of the committee members from the different cultural communities to help us convene community representatives. We had meals together. We asked questions, and we listened to the answers. I tried to attend as many of them as I could, to be present to demonstrate the importance of the conversations–even if they were conducted in another language. There was someone who was taking notes in English of what was being said or translators would whisper in my ear so I could get an idea of what was going on. There was a lot of commonality between the answers we got from the various communities. We thought that maybe we were going to hear a lot of differences, but mostly there were commonalities. There were different needs for different neighborhoods, of course, but people overall were very resilient. Connection to one’s culture is a source of great strength for our residents.”

Musicant went on to describe the impact that residents’ engagement had on the strategy development. “[Their insights] really influenced the kind of words we use in our vision, in our mission, and most importantly the way we think about the definition of health and the way we do things. [There was] also a deep richness that comes from not just bringing your idea forward in a ‘focus groupy’ kind of way, where you tell people ‘we are going to do this’ and see if they like it or not.. It was just us stepping in this wide open way of engaging residents that was changing [how we do things].”

Example 3: Miami, FL

Dr. Roderik King, assistant dean of public health education at the University of Miami Miller School of Public Health, worked with the Florida Department of Health to build the Liberty City Community Collaborative and implement its local health action plan. He and others created space for residents to participate by using a simple and inclusive co-design process. “We use a lot of different tools that I think helped our [resident] engagement [practices],” said King. “One of the tools is called a co-design call. Using a conference line that we set up for residents and stakeholders, and everybody interested in contributing to designing the [community] meeting, [we provided an explicit opportunity for them to] jump on the call. It is usually an hour, and the whole point of that call is to design our work together [and] come up with the smarter and more effective solutions.”

We’ve only just begun to understand what makes resident engagement work well

It’s important to say that the resident engagement approaches we’ve been discussing in this series are not panaceas. Resident engagement is challenging work, and we are only just beginning to sort through how to best create the conditions for them to lead. It’s critical to prepare your partnership members to effectively manage and hold any challenges as signs of progress–after all, they wouldn’t exist if you weren’t trying.

Have you engaged residents in ways that ensure their sense of belonging, trust, and/or power? If so, how? We’d love to learn more about your successes and struggles, and how this approach has impacted your work in the comment section, below.